History

1893 r. – 1945 r.

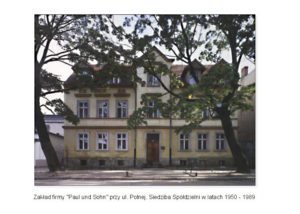

The former headquarters of „Julius Paul und Sohn” in Bolesławiec, 19 Polna Street

1950 r. – 1989 r.

The headquarters of the Artistic Handicraft Cooperative „Ceramika Artystyczna” in Bolesławiec, 19 Polna Street

Signatures of the Bolesławiec ceramics

Impressed mark

Work Co-operative Society

of the Folk and Artistic Industry

Bolesławiec, 1954 – 1963

Impressed mark

“Artistic Ceramics”

Bolesławiec, since 1963

(also interchangeable with mark 1)

Stamped mark

“Artistic Ceramics”

Bolesławiec, 1963 – 1995

Engraved signature

Elżbieta Piwek-Białoborska

Wrocław – Bolesławiec,

thesis 1952

Engraved signature

Elżbieta Piwek-Białoborska

Wrocław – Bolesławiec,

thesis 1952

Impressed signature

Halina Draczyńska

Wrocław – Bolesławiec,

thesis 1952

Impressed signature

Halina Draczyńska

Wrocław – Bolesławiec,

thesis 1952

Impressed signature

Halina Draczyńska

Wrocław – Bolesławiec,

thesis 1953

Impressed signature

Gabriela Hoffman-Śleżewska

Wrocław – Bolesławiec,

thesis 1952

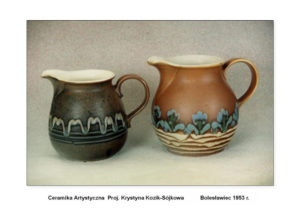

Engraved signature

Krystyna Kozik-Sójkowa

Wrocław – Bolesławiec

thesis 1952

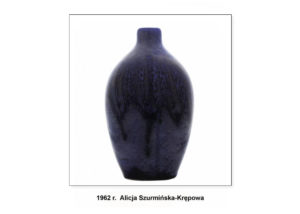

Engraved signature

Alicja Szurmińska – Krępowa

Wrocław, 1953

Painted signature

Wanda Matus

Bolesławiec, 1974 – 1990

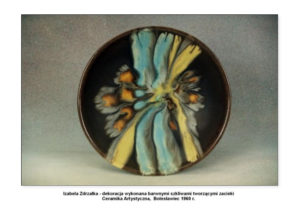

Engraved signature

Izabela Zdrzałka

Bolesławiec, 1952

Painted signature

Izabela Zdrzałka

Bolesławiec, 1953

Engraved signature

Izabela Zdrzałka

Bolesławiec, 1954

Painted signature

Izabela Zdrzałka

Bolesławiec, 1955

Painted signature

Izabela Zdrzałka

Bolesławiec, 1958

Painted signature

Izabela Zdrzałka

Bolesławiec, 1960

Painted signature

Alicja Szurmińska-Krępowa

Bolesławiec, 1959

Painted signature

Bronisław Romanowski

Bolesławiec, 1982 – 1984

Painted signature

Bronisław Wolanin

Bolesławiec, 1974

Stamped mark

“Artistic Ceramics”

Bolesławiec, since 1995

designed by B.Wolanin

Stamped mark

“Artistic Ceramics”

Bolesławiec, since 1995

designed by M.Ochocki

Stamped mark

“Artistic Ceramics”

Bolesławiec, since 2000

designed by M.Ochocki

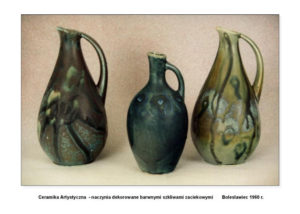

The “Artistic Ceramics” stoneware in Bolesławiec

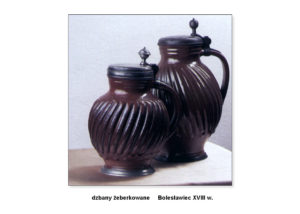

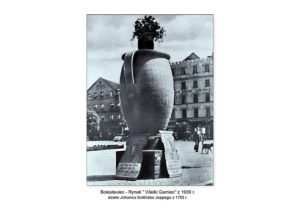

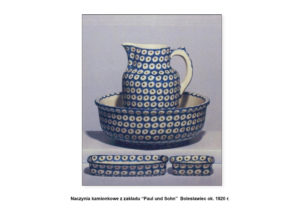

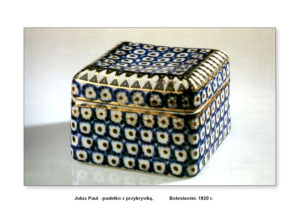

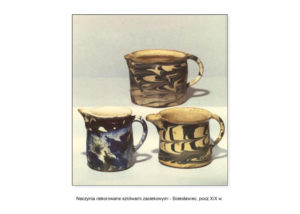

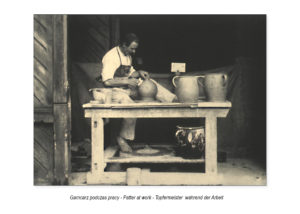

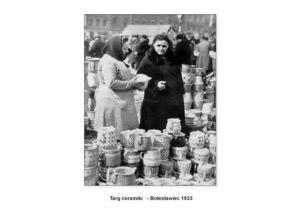

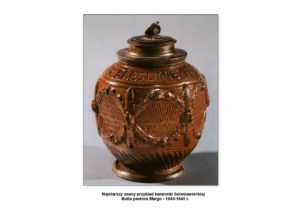

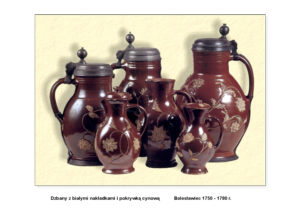

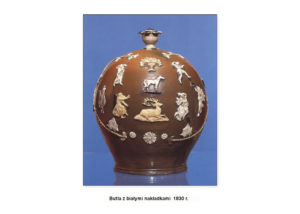

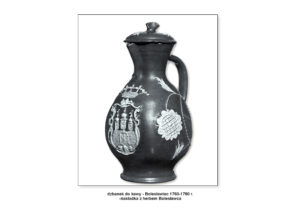

The rise of ceramic craft in Bolesławiec goes back to the medieval times. The ceramic techniques started to flourish in the 18th century with the introduction of a new decoration method, brown glaze with white patterns, which made the ceramics from Bolesławiec a well known and highly desired commodity throughout the whole Europe, including even royal courts. In the second half of the 19th century faience gained popularity on the European market. The expansion of a new material was a real challenge for potters from Bolesławiec who started to use colourful, stamp ornaments against a white background to make their products more attractive. The traditions of fine Bolesławiec ceramics are continued today and the mentioned stamp method has been in its prime time in the last decade.

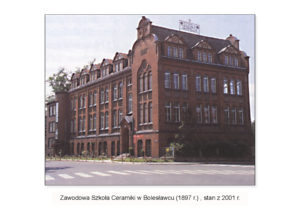

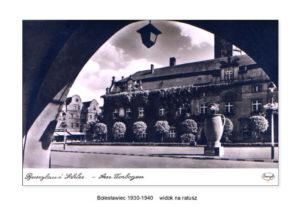

In the end of 19th century a ceramic school was founded in Bolesławiec which educate good craftsmen and artists of sophisticated taste.

Faced with such a great challenge like the necessity to get the Bolesławiec surroundings off the ground quickly and efficiently after World War II, Poland did not have an easy task to come to grips with. As an active ceramic centre with many hundred years old tradition, the Bolesławiec area had been famous for its stoneware appreciated on the European markets for both its usefulness as well as its artistic values. The local clay contained a great deal of flux, first of all silicon, feld-spar and at times kaolin impurities. The ceramics madę of it, provided the sintering temperaturę was between 1100 and 1300 °C, had a dense, durable and partially yetrified structure. It was resistant to temperature, moisture, as well as to chemical and mechanical influences.

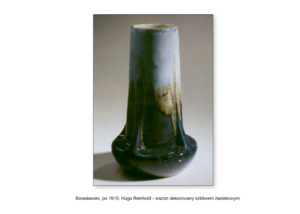

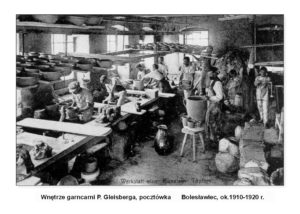

Destroyed in nearly 80%, deserted by the aboriginal creators of the ceramic tradition, with numerous big and small plants deprived of their machines and eąuipment, Bolesławiec was not only a challenge but also a land of promise. Right after the war stock was taken in the plants, the degree of their destruction and the chance of revival of the production assessed. Tadeusz Szafran, an outstanding potter, took the latter upon himself within the Lower-Silesian Operating Group. He graduated the College of Fine Arts (ASP) in Kraków and the Ceramics University in Hohr, and lectured at the Institute of Applied Arts in Weimar. In the interwar period hę dealt with pedagogy in Kraków and simultaneously worked as the technical director in the Porcelain Facto-ry in Chodzież. With his versatile background and orientation Tadeusz Szafran was predestined to be appointed to this office. Soon (1946) he put on stream the old Reinhold plants at ul.Górne Młyny in Bolesławiec.

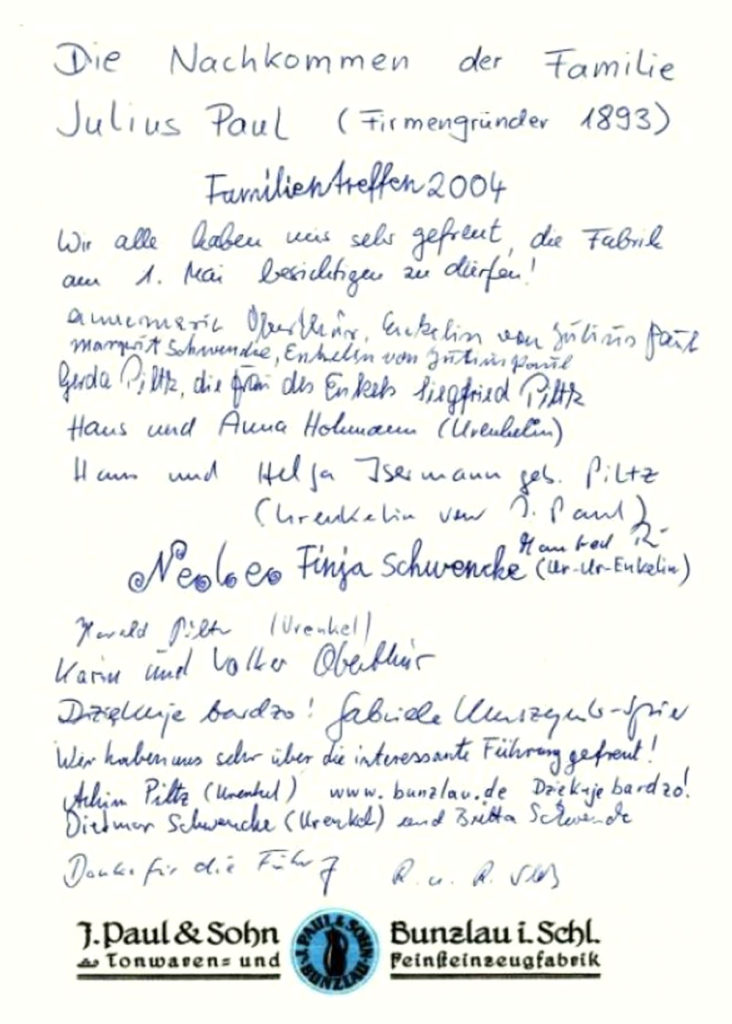

The previous “Julius Paul und Sohn” plant at ul.Polna was initially lucky neither with good managers nor with technologists. At the beginning of 1949 the Workers Productive Cooperative of Ceramics and Building Services was founded but ceased to produce already in July and the supervisory board declared it bankrupt. This resulted ultimately in taking it off the register of cooperatives. In 1950 the State Committee of Economic Plan-ning transfered the by that time already deserted plant to the Stateowned Cooperative Centre of the Folk and Artistic Industry (Cepelia), its voivodeship branch in Wrocław.

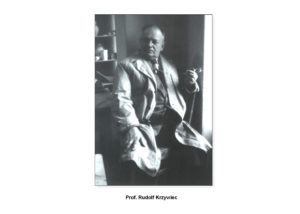

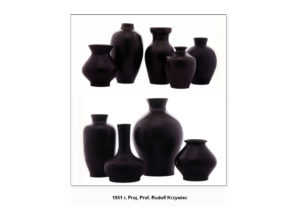

The State University of Fine Arts (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Szutk Plastyczych – PWSSP) in Wrocław contributed immensely to the successful implementation of the enterprise. Not to overestimate was also the initial help of Mieczysław Pawełko (1908-1962) and sińce October 1950 that of Rudolf Krzywiec (-1885-1982). Thus history came fuli circle: it was them who during their studies took advantage of the experience and the profound knowledge of Julian Mickun (l884-1972), who graduated the Public Technical College (Miejska Szkoła Zawodowa) in Bolesławiec before 1918. In the interwar period he and his brother, Władysław ran a tilery at ul. Czerniakowska in Warsaw for a living. In the tilery there were smali furnaces assembled for burning ceramics in high temperatures. This way he popularised stoneware, which at that time hardly existed in the national culture. In 1926 Karol Tichy employed him as instructor and technologist in the ceramic study at the College of Fine Arts (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych – ASP) in Warsaw. Later on Rudolf Krzywiec will write about him: His goal and desire was Polish artistic ceramics of good quality. He also commented on his student years at the college (ASP): “Prof. Karol Tichy was in charge of fine arts – form and decoration. Julian Mickun was responsible for the technical side. It was Julian Mickun who made the students acquainted with the technological basics of ceramics. (…) The first works written under his leadership came as revelations”. Apart from his involvement in the college and the artistic ceramics, Mickun was a cofounder of the ceramic group Ład and offered his tilery for its headąuarters. The following belonged among others to the group: Rudolf Krzywiec, Mieczysław Pawełko, Julia Kotarbińska (1895-1979), Wanda Golakowska (1901-1975). Thus the college in Bolesławiec indirectly contributed to the respect paid for the ceramic handicraft later on. Technology was especially important as a significant form factor by artists who after the war played a great role in the revival of the earlier ceramic magnificence of the city on the Bóbr River. First it was Julian Mickun’s students, Mieczysław Pawełko, Rudolf Krzywiec, Julia Kotarbińska, then their own students, Bronisław Wolanin, and finally the next generation, Wanda Matus.

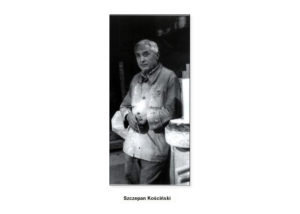

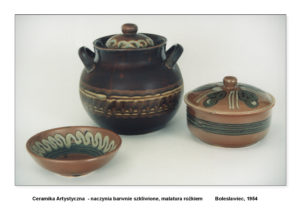

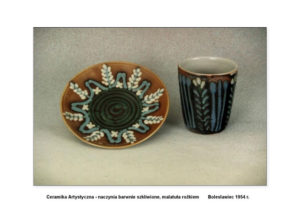

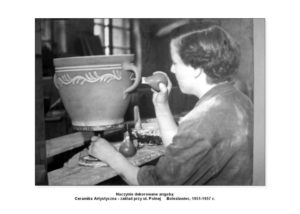

Let’s come back to 1950. The university in Wrocław grants its experienced technologist and furnace builder, Szczepan Kościński (1897-1970), leave of absence for the sake of working in Bolesławiec. It was Kościński who organised and set the production in motion. In the newly set up plant the students served their apprenticeships and designed new patterns of the ceramic forms for the factory. Here Halina Draczyńska, Irena Dródż-Hyży, Gabriela Hoffman-Śleżewska, Krystyna Kozik-Sójkowa, Elżbieta Piwek-Białoborska, Ewa Panufnik-Dworska did their thesis in 1952-1962. Here was also a working place for the people like Alicja Szurmińska-Krępowa (1953-1955, 1958-1959), Krystyna Kozik-Sójkowa (1953-1957), Izabela Zdrzałka (I95I-I957), Halina Draczyńska (l953-1955), and for a short time Halina Feret-Karczewicz and Dionizy Strzelbicki. Despite the fact that Szczepan Kościński ceased to work at the plant and the cooperation with the Wrocław university was declining, the experience had a positive impact on the development of the Bolesławiec ceramics plant. From now on it will have their own designers and as one of few factories it will be able to pride itself on its own sophisticated artistic profile oscillating somewhere between the local tradition and the trends of the modern design. It was controlled and taken care of by the artistic supervisor whose office was introduced as a regular one in 1952. Since then the design as well as the paint shop were supervised by a well-educated artist and designer supported by an experienced technologist. This ranked Bolesławiec among reputable plants and ensured an appropriate artistic level as well as that of production technology. In order to gurantee its products a commercial success, the modern ceramic industry has to be based on its own unique design. That is why the designers play a particular role in the functioning of all reputable factories. Analysing the post-war Bolesławiec plant from this point of view one can see how the design has been developing during the last 50 years, not only in Bolesławiec but also in other places. Obviously a well-educated designer improves the ąuality of the products and guarantees the introduction of the newest design tendencies from all over the world.

Izabela Zdrzałka became the first artistic supervisor (I95I-I957). She worked initially in the paint shop. After 1952, having defended her thesis at the PWSSP in Wrocław, Izabela Zdrzałka accepted the office of the artistic supervisor. This was a pioneer time for the factory during which the experience gained at the university had to suffice for both designing of new patterns and new assortment of dishes, as well as for solving purely technical or technological problems. The extension of the assortment allowed to replace in the course of time the forms formerly belonging to the Germans with the own ones. However, it was Izabela Zdrzałka who had to handle all these matters at once. She initiated the production of about a few dozens of her own projects of dishes. At the beginning the proportions were compact and conventional and the artist concentrated mainly on decorating the German as well as her own forms. For ornamentation she used not only the little stamps or sponge so typical of Bolesławiec, but also introduced painting with enamel by the means of a stake, which she then replaced with a “pear”, and graffito. She painted and engraved folk motifs and life scenes. Upon the revival of the relationships with Western European countries, the projects of the forms became much more unconventional. The dishes could be asymmetric and the ornaments abstract: all kinds of patchy (colourful design) or strip patterns, which referred to the tfends in the applied art of those times.

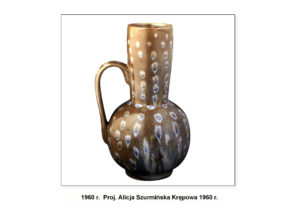

The successor of Izabela Zdrzalka was Alicja Szurmmska-Krępowa (l953-1955 and 1958-1959) who took over the office of the artistic supervisor in 1958, She designed forms of dishes and painted the products. She used the stamp and stake methods for decoration. The dishes decorated with a stake would depict folk motifs. By the means of forms she also made texture impressions. The glaze applied would be uniform and rubbed. Szurmińska-Krępowa had an excellent feeling for shape. Later on she too yielded to the more general influences – more unconstrained compositions of vases, carafes or ashtrays, asymmetry and morę versatile solid effects. For decoration she would prefer to use more often colourful design glazes and painted organie abstract motifs.

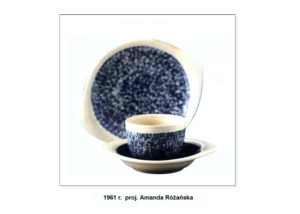

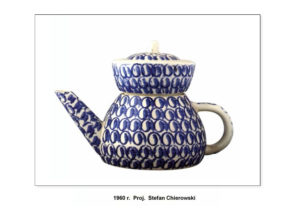

In 1960 Amanda Różańska, a graduate of the university in Wrocław, was appointed the next artistic supervisor. She designed numerous dishes of daily use: troughs, ashtrays, au gratin dishes, side-dish plates, drinking sets, vases and little playful plastics. Some of the dishes were combined with little baskets or wicker trays. Amanda Różańska attached a great importance to shapes. It was for her precision and elaborateness that her projects were so special. Plates for instance could be rectangular, triangular or spindle-shaped. The symmetry of some of them would be disturbed. For ornamentation she would use little stamps, sponge, and flat impressions or those morę similar to relief. Simultaneously Różańska used widely glazes accessible at that time. The production of many projects delivered either by the Institute of Applied Design (ball-shaped carafe, 1954) or by artists was initiated in that pioneer afterwar period. Dishes of some, few but still, designers are manufactured even today.

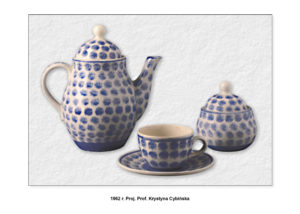

The following belong to this grop: Maria Ałkiewicz, Stanisław Barnaś, Tadeusz Boroński, Leokadia Bożek, Stefan Chierowski, Krystyna Cybińska, Jerzy Cynke-Widalis, Aniela Daszuk-Kardasz, Danuta Duszniak, Adam Dzień, Kazimiera Hulanicka, Henryk Jędrasiak, Sandor Koczor, Bogdan Kiziorek, Teresa Kopyciak-Forowicz, Sylwia Kostrzyńska-Wierzchowska, Julia Kotarbińska, Rudolf Krzywiec, Henryk Lula, Halina Łepkowska-Giecewicz, Lidia Oleśniewicz, Adam Sadulski, Ryszard Stryjec, Ryszard Surajewski, Andrzej Trzaska, Maria Waltratus-Rybak, Hanna Żuławska.

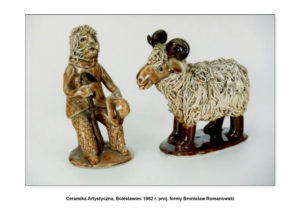

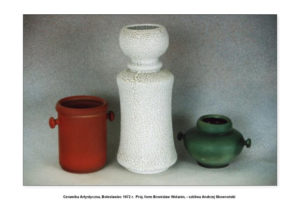

And other designers: the plant modeller Zdzisław Pietrzakowski and Bronisław Romanowski, modeller and creator of unique devil and ram images, as well as of life scenes, (1950-1954, 1958-1974). Later, m the seven-ties and the eighties the plant became entirely independent in terms of design and only occasionally some projects from outside would be used for manufacturing (designed by Karen Park or Irena Lipska-Zworska).

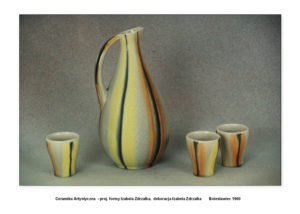

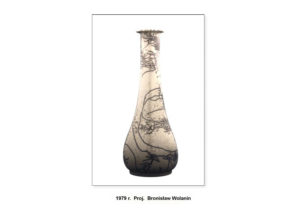

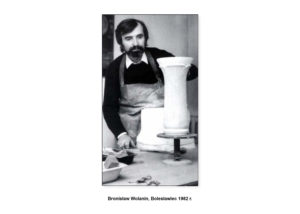

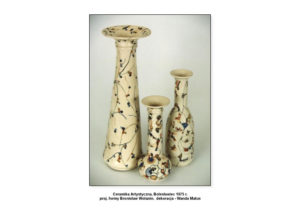

The artist who has worked in the Bolesławiec plant the longest (1964-1980 and since 1985) is Bronisław Wolanin. From the very beginning hę has worked as the artistic supervisor He graduated the Wrocław university where hę worked in the study of Julia Kotarbińska. He was equally successful at drawings as well as at ceramic sculpture. His versatile interests in different pe-riods of his artistic career intermingled and madę him experiment with forms and ornaments. At the university Wolanin was taught the neat aesthetics which boiled down to a harmonie bond of functionalism of the product with its smartness and the simplicity of shape and decoration. On the other hand he came across the abun-dant and versatile local ceramic tradition which reconciles the newest trends of the world design of the twenties and thirties as well as the nearly folk or historie ones from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It is the reconciliation of this tradition with the modern trends that Wolanin has devoted his entire career as a designer.

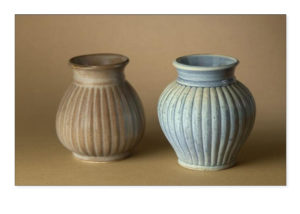

At the beginning his numerous dish forms, plaquettes and miniatures referred to the oldest heritage: to grooved and ball-shaped pitchers covered with a clay glaze and white layers depicting plants’ or heraldic motifs. He attempted to achieve all these effects by the means of appropriately prepared casting moulds. The details of the reworked and modernised motifs and ornaments were very neatly elaborated and the reliefs professionally rubbed. Thus the surface of the dishes differed in the colour saturation of the glaze and gained an attractive glitter.

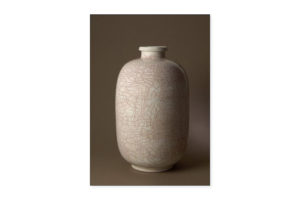

In the seventies this youthful infatuation with tradition yielded to rigidity and simplicity. Putting together different stereonietric figures in his forms, Wolanin made every attempt to achieve sophisticated proportions of their particular elements. Subordinated to the strictness of the graphic sign, the drawing of the profile of his dish would be now extremely subtle aesthetically. Such puristic targets could be achieved with the great support of the outstanding specialist and technologist, Andrzej Skowroński. Their fruitful co-operation compensated for the shortage of diverse glazes.

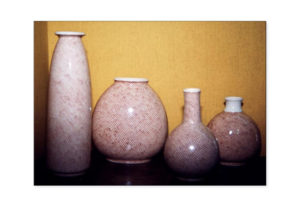

The unique effects of Wolanin’s products resulted from his gradation of shiny, mat or rough glaze. In this period the artist went back to his graphics but never literally. Wolanin took advantage of his experience and transfered them rather imperceptibly. Thus hę created sets of dishes painted in dots with sepia or cobalt. The entire surface was dotted evenly just like it used to be done in the inter-war period by the means of little stamps. Besides Wolanin used the technique popular at his university, craquele. Its results were astonishing. It used the net of fractures in the potsherd obtained in the furnace or by the application of crystalline glaze. In both cases a skilful juxtaposition of the ornamented surfaces with the even ones gave the composition much more expression that reminded of secession or of the Japanese painting.

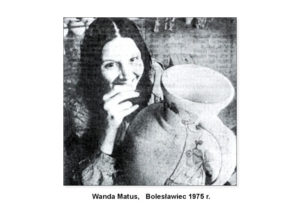

The works painted by Wanda Matus (1972-1987), another graduate of the university in Wrocław, make a similar impression She did her ceramic specialisation in the study of Krystyna Cybińska. Sporadically she designed ceramic forms. From 1980 until 1987 – at that time Bronisław Wolanin was working in the “Bolesławiec” plant in Bolesławiec – she worked as the artistic supervisor. In the seventies Cybińska became known as an extremely gifted and original ceramic painter. Her very personal, created without restraint, delicate and capricious compositions of fanciful plants and flower motifs placed against the white background and harmoniously composed with the rest of dish were unprecedented. She used an even glaze and at the same time differentiated engraving. Occasionally she also carved the surfaces of her cerations. In most cases she would decorate the forms designed by Wolanin.

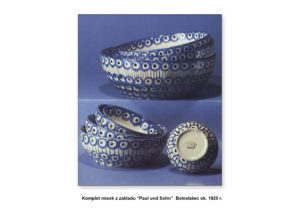

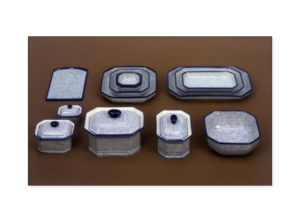

The innovations in decorating the dishes described above required a personal engagement of the artists and were very time-consuming. They were also too difficult for the team working in the paint shop as to keep up with the increasing demand for the Bolesławiec products. The dishes with such ornaments became ephemeraL To their rescue came the local tradition. Stamp or sponge decorating which was typical of the inter-war period and applied – but not prevailing – in the plant after the war brought on many technological problems. The stamp method became more popular after 1974- The revival of little stamps coincided with the fashion for the old, as well as with the growing interest of collectors not only in Poland but also elsewhere. Its demand for the old “bunzloki” was increasing morę and more. Exactly at the same time the Ceramics Museum (Muzeum Ceramiki) in Bolesławiec started to collect and exhibit the late ceramics from before 1945. Originally Bronisław Wolanin decorated his own forms with stamps but since the ornaments had to be adjusted to the shape of the dishes, hę soon began to create new formulas still corresponding in different ways to the tradition.

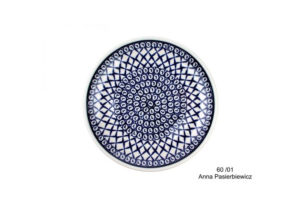

In 1974 a designer of decoration, Anna Pasierbiewicz began to design decorations made with stamp method. At the beginning, the stamps were cut from rubber and then from sea sponge. Except the famous decoration no. 70 which was the recognizable pattern, other decorations were created with motifs of checks, rings, rosettes.

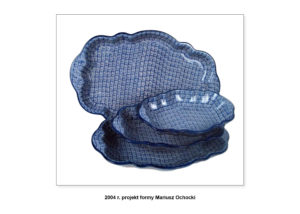

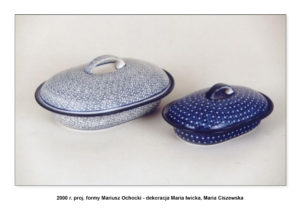

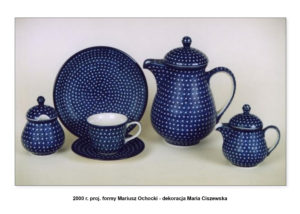

The fifty years of existence and work of the design department in the Bolesławiec plant have significantly contributed to the development of ceramic forms. The artistic output of the Bolesławiec team will surely serve the next generations. There are still new patterns being created not only by Wolanin but also by the artist in charge of the company’s advertisement, Mariusz Ochocki. Ochocki has been employed since 1991.

Next to the most frequent ornament, the traditional eye of a peacock s tail-like pattern, there is also a whole range of new ones loosely referring to their predecessors: patches or strips. Forms decorated with cobald are the most predominant and popular ones. These are the products the plant can pride itself on. Light blue is the most frequently applied colour but more and more desirable are also greens, browns and reds.

In the seventies the Western European traders became more interested in the products of the plant what strengthened the tendency to apply the stamp method. It has been the most prevailing method of decoration.

Since 1989 when the factory was transferred from ul.Polna to the newly raised, modern and bigger building at ul.Kościuszki, the production capacity has significantly increased. This enables the plant to satisfy the evergrowing demand. Thanks to the technological perfection and to the great and diverse range of forms and ornaments, the plant’s products are awarded in both Polish and international competitions. Next to the traditional distribution channels like Germany, England, France, Holland or United States, “Bolesławiec” is becoming well known in exotic countries as well, i.e. New Zealand or Scandinavia. The latter is a demanding, hermetic and difficult market, even if only due to the worldwide fame for its own design.